CONFESSIONS OF A NEURASTHENIC

WEBMASTER'S NOTE: This work is presented for historical interest and subject background only. Many of the conclusions, attitudes, and treatments discussed here are those of an "expert" of another era, many of which have been overturned by science or are not acceptable in today's world.

CHAPTER V.

TRIES TO FIND AN OCCUPATION CONDUCIVE TO HEALTH.

Indecision marked my life and character and I had no confidence in myself. Yet I realized that I had an active brain, only that it was misdirected and running riot. To correct years of improper thinking and living may seem easy as a theoretical problem, but if one should find it necessary to put the matter to a practical test on himself, he discovers that it is like diverting the course of a small river.

I was sensitive and thought a great deal about myself. Often I entertained the effeminate notion that people were talking about me, when I ought to have known that they could easily find some more interesting topic of conversation. I always went to extremes. I was up on a mountain of enthusiasm or down in the slough of despondency; always elated or depressed; optimistic beyond reason or submerged in pessimism; always the extremes—no happy medium for me. I never met anything on half-way grounds.

[Pg 28]Being now of mature years, I realized the necessity of settling down to something, if for no other reason than that I might gain a little more stability of character. Accordingly, I accepted a position as bookkeeper in a flour-mill. I remained at it longer than I ever had at anything. After a few months, however, it seemed that the close confinement indoors did not agree with me. Sitting in a stooped position over books produced a soreness in the muscles of my back and I imagined that I had incipient Bright’s disease. I have since learned that the kidneys are not very sensitive organs and seldom give rise to much pain even in the gravest disease. I read up on kidney affections in the almanacs—oh! what authority!—and as I had about all the symptoms, I thought it best to put myself on the appropriate regimen. I began drinking buttermilk, taking it regularly and in place of water and coffee. I had read that sour milk was also conducive to longevity, and that if one would drink it faithfully he might live to be a hundred years old. A friend to whom I had confided this information said that between swilling down buttermilk a hundred[Pg 29] years and being dead, he preferred the latter.

There was a decided improvement in my case in some respects, but I began to acquire new and different symptoms, mainly from reading medicine advertisements. My name had been seized, as I learned later, by agencies, and was being hawked around to charlatans and medicine-venders. Yes, some one had put me on the “invalid list,” and when[Pg 30] once your name is there it goes on, like the brook, “forever.” The medicine-grafters barter in these names. I have been told that for first-class invalids they pay the munificent sum of fifty cents per thousand! I think that a thousand of my class ought to be worth more—say, six bits! It seemed that I was on several different lists, among them being “catarrh,” “neurasthenia,” “rheumatism,” “incipient tuberculosis,” “heart disease,” “kidney and liver affections,” “chronic invalidism,” and numerous others. I was fairly deluged with letters begging me to be cured of these awful diseases before it was forever too late.

One of the symptoms common to all these grave troubles was “indisposition to work.” I knew that I had always suffered from it to the very limit, but I did not know that it was dignified by being classed as such a common disease symptom. I also had a number of other abnormal feelings that were common to most of the ailments described. For example, at times I had “singing in my ears,” “distress after eating too much,” “self-consciousness,” and “forebodings of impending danger.” I[Pg 31] always experienced great fear lest one of these “forebodings” overtake me unawares.

These letters were always “personal,” although the type-written name at the top did not look exactly like the body of the letter. Possibly they may have been, in advertising parlance, “stock letters.” They purported to be from kind-hearted philanthropists who were in the business of curing people simply because they loved humanity. Some of them were from persons who had been cured of something and who now, in a spirit of generosity, were trying to let others similarly afflicted know what the great remedy was.

While I realized that these advertisements were base lies, gotten up to deceive the sick, or those who think they are sick, and to take their money in exchange for dope that was worse than useless, yet the diabolical wording of those sentences affected me in a queer and inexplicable way. The psychologist would, perhaps, call this a subconscious influence. When a person gets the disease idea rooted deeply in his mind, as I had it, he is kept busy watching for new symptoms. It is no trouble[Pg 32] at all to get some new disease on the very shortest notice.

As a more active occupation seemed necessary for me, I was trying to study up something new to tackle. Doctors had told me that I needed to be out in the open air where I could get plenty of exercise and practice deep breathing. This agreed with me and I seemed to be gaining in strength, but I came to the conclusion that I might as well turn my exercise into a useful channel; so I went out into the country and hired myself out to a farmer. Here I got, in a very short time, a bit more of the “strenuous life”—a late term—than I had bargained for. We had to get up at four, milk several cows, and curry and harness the horses before breakfast. We then kept “humping” until sunset, except during the hour we took for dinner. On rainy days we were supposed to work in the barn, greasing harness, shelling seed-corn and “sifting” grass-seed. That old farmer seemed to realize the verity of the old couplet:—

“Satan finds some mischief still,

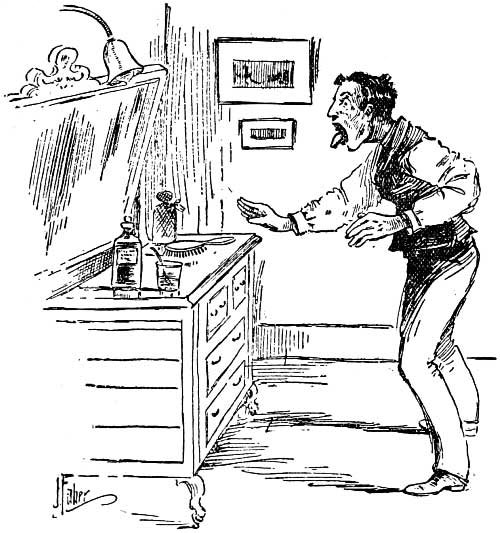

For idle hands to do.”Looking for new symptoms.

[Pg 34]The reader will readily imagine how hard labor served me. My muscles were as sore as if I had been the recipient of a thorough mauling. I tried to stand the work as long as I could, for I thought it would, like the other remedies prescribed for me, “do me good.” I had been there a week (it seemed to me an eternity) when, one morning, I was so sore and stiff that I could not get out of bed. One of the other hired men came to my rescue and gave me a thorough rubbing with liniment, after which I was able to crawl down to breakfast. The old skinflint of a farmer then had the audacity to discharge me, saying that he “didn’t want no dood from the city monkeyin’ around in the way, nohow.”